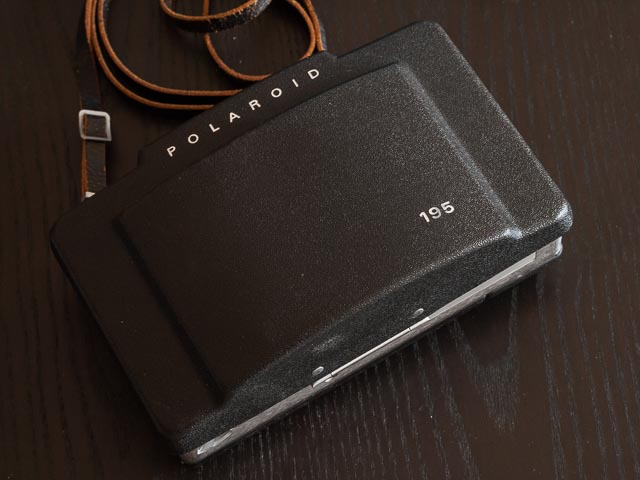

Polaroid 195

Polaroid introduced their first camera in 1947 (the Polaroid 95). These early camera used Polaroid roll film which has not been available in any form for many years. Polaroid roll film came with separate rolls of negative and print material, which made them quite complicated to use. Polaroid stopped making their roll film in the 1980s, so even when you do occasionally see it on eBay it’s now far to old to be of any use. So the oldest Polaroid cameras that you can actually use to day are the so called ‘pack-film’ cameras. The first of which (the Polaroid 100 Automatic) was launched in 1963. Pack film had the negative and print material packaged together in one pack which made them much more convenient to use, though you still had to manually pull the photograph out of the camera, wait for 60 seconds or so (depending on the type of film) and then peel the negative off the print (hence the other common name for this film: ‘peel-apart’).

There is a rather confusing array of model named for these pack-film cameras, but the basic system isn’t too hard to grasp: most cameras had 3 digit model numbers, and the first digital is the generation number, so 100 numbers are first generation, 200 numbers are second generation and so on. And from the second generation on, the second 2 digital tell you how far up the range you are, so the 250 is better than the 240, which is better than the 230 and so on. Of these model the most desirable are the ones with model numbers that end in 50. These models had high quality 3 element glass lenses and superb Zeiss made viewfinders with rangefinders integrated into the main viewfinder window and parallax corrected bright-line frames. The exception to this rule are the 100 series (the original ‘100’ model is the top of that series) and the 300 series (where there was a model 360 above the 350 model which featured an electronic flash gun with rechargeable batteries).

The other main exceptions to look out for are the professional models: the 180, 190 and 195. These cameras are particularly desirable in many ways. The all feature mechanical and manual exposure systems that require no batteries (finding the correct batteries for the automatic models is always a challenge!). They also all feature superb 4 element lenses made by Tomioka. The 180 and 195 models also feature mechanical development timers which means they are totally free of batteries (the 190 is very similar to the 195 model but features an electronic timer). There are two main differences between the 180 and 195 models: the 180 features the same superb Zeiss rangefinder as the 250, 350 and 450 automatic models described above, while the 195 features a cheaper viewfinder with separate rangefinder and viewfinder windows. But the 195 counters with an ultra fast f/3.8 114mm lens against the 180’s f/4.5 114mm lens. The 195 is also the more recent model so 195s tend to be in slightly better cosmetic and mechanical order.

So to summarise, if you are looking for an automatic pack film camera look out for the 250, 350 or 450 models, and if you want one of the manual professional models look out for the 180 or 195 models, with the slight preference going to the 195.

Now, photographers used to 35mm cameras may well be thinking at this point that f/3.8 doesn’t sound ultra fast. But you have to remember that the larger the format the shallower the depth-of-field, and Polaroid pack-film represents a very large format indeed… about half way between a typical medium (e.g. 6x7cm) and large (e.g. 4x5”) formats. In fact, in terms of depth-of-field, f/3.8 on a Polaroid pack-film camera is equivalent to something like f/1.4 on a 35mm camera. This is why many cheaper Polaroid cameras, which have pretty basic focusing systems, are often limited to really small apertures, like f/8 or f/11… that is the only way to ensure there is enough depth-of-field to get sharp results with such basic focusing systems. An aperture of f/3.8 can be quite tricky to focus properly even with a high quality rangefinder system like the one fitted to the 195.

Polaroid 195 detailed photos

This is the Polaroid 195 folded and ready to be fitted with it’s front cover.

I have never seen a lens cap for the lovely 114mm f/3.8 Tomioka lens, but the camera comes with a plastic cover that covers the whole of the front of the camera.

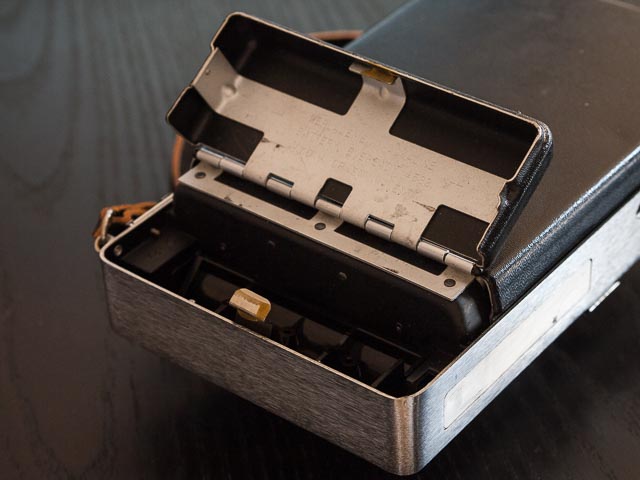

This is the back of the camera. You can see the separate windows for the rangefinder and viewfinder. (Note that I have now replaced the original 195 viewfinder with the lovely Zeiss viewfinder from a Polaroid 350. This viewfinder has a single window for both framing and focusing.)

You can also see the mechanical development timer that means the 195 is completely free of batteries. Note that the timer normally feature numbers representing seconds but these seem to have worn of this camera. A previous owner has painted on dots at each 15 second interval instead.

The body of the 195 is the same as the body of the 250, 350 and 450 automatic cameras, and so it features the same battery compartment from those cameras, even though it doesn’t actually need batteries!

The 195, in common with most pack film cameras, is focused using the two tabs at the top of the camera. On the 195 these tabs are marked in meters.

My Polaroid 195 system

#595 Filter Kit

Polaroid made many accessories for their pack film cameras. The accessories designed to fit on the lens, like filters and close up lenses are different for the professional type camera because the lenses on these camera are much bigger. The #595 Filter kit works with all the professional models and includes the #596 ‘Cloud’ or orange filter for bringing out clouds in blue skies with black and white film, the #597 UV filter and the #598 lens shade.

#1951 close-up kit

This kit include a close-up lens and a set of goggles that fit over the 195’s viewfinder. The similar #593 close-up kit includes the same close-up lens together with goggles for the Zeiss finder that the 180 model features.

Very similar ‘portrait’ kits were made for both the 195 and 180 models that had a less powerful close-up lens.

#192 Self-timer

This wonderful mechanical self-timer works with both automatic models and the professional manual models. It makes a fantastic sounds as it works like an angry wasp!

Here is the #192 self-timer fitted to the 195.

Using the Polaroid 195 in the field

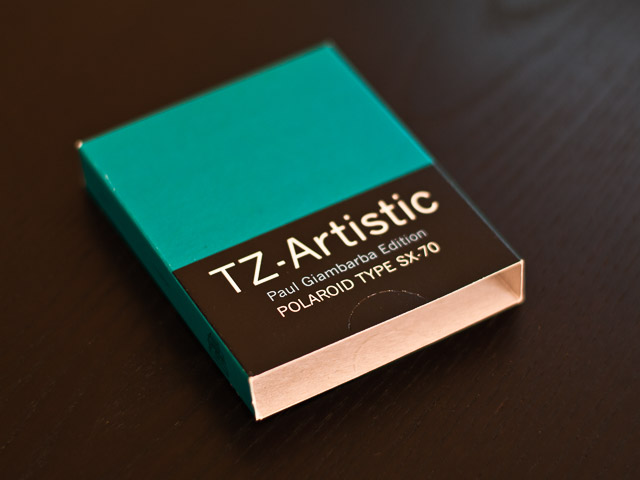

The problem with using any pack-film camera in the field is that the prints take several minuted to dry when you have peeled the negative off the print. If two prints touch while the are drying they will stick together and be ruined. I use these Paul Giambarba designed boxes that The Impossible Project use as outer packaging when selling SX-70 TZ Artistic film to store Type 100 Polaroid prints while they dry.

When traveling the Paul Giambarba boxes fold neatly next to my Polaroid 195 in my camera bag.

When I'm ready to take photographs the Polaroid 195 goes around my neck and the Paul Giambarba boxes are unfolded to form a kind of portable drying rack in my bag. Problem solved!

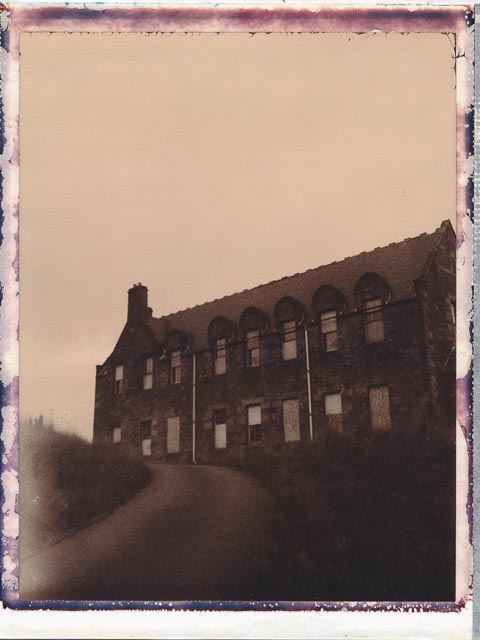

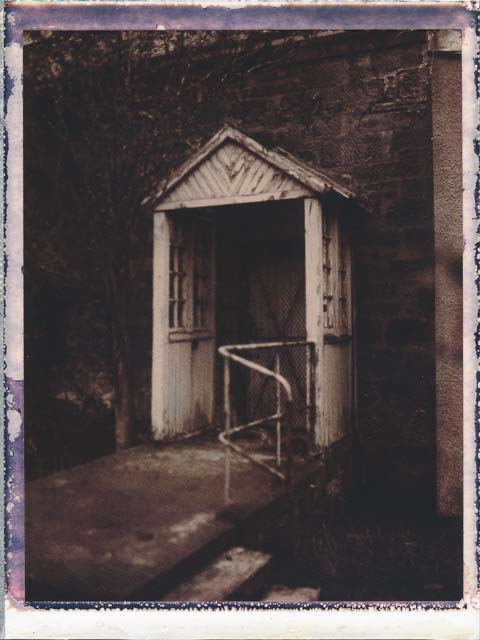

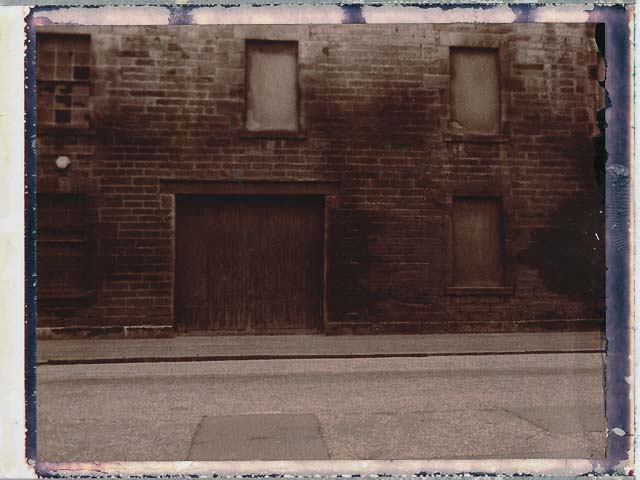

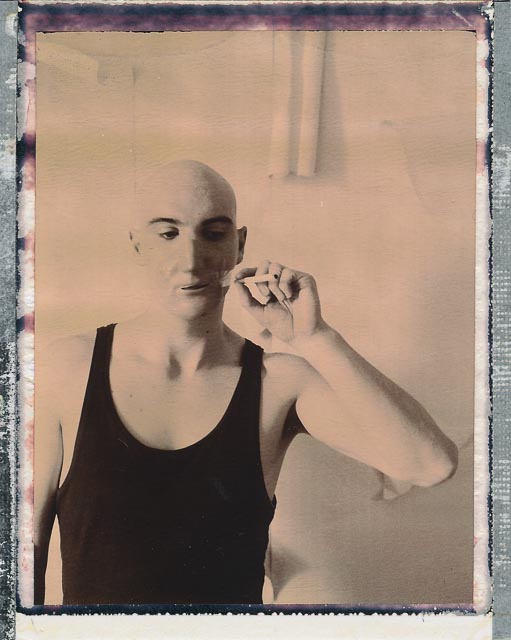

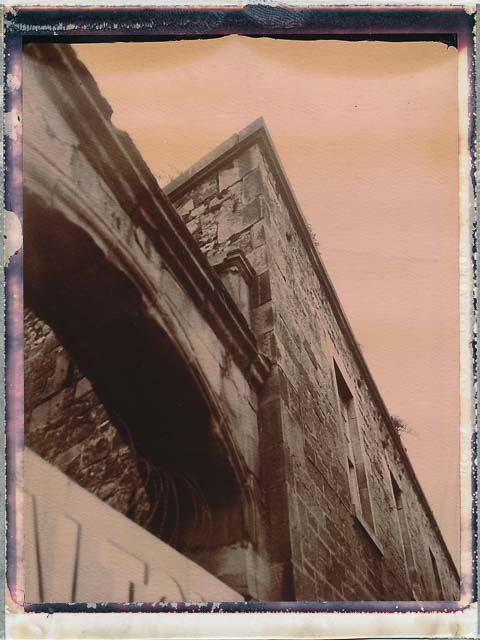

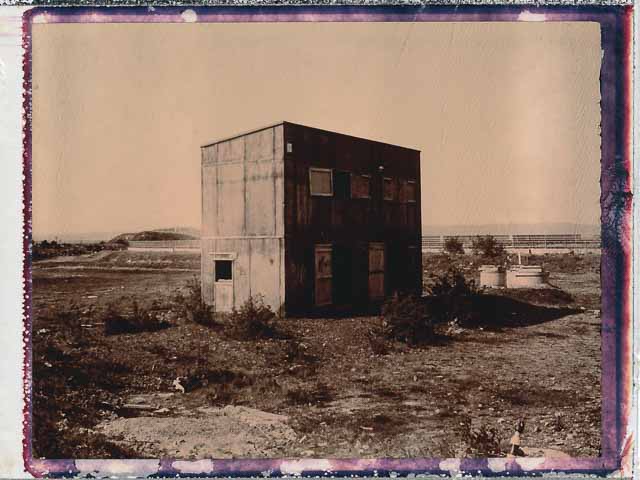

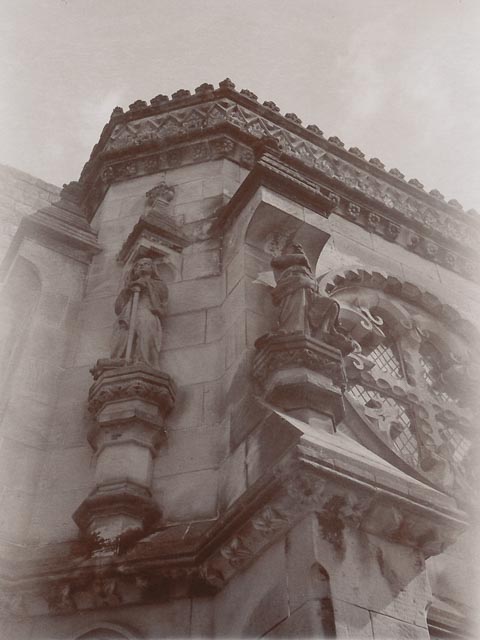

Photographs taken with the Polaroid

Polaroid 100 Chocolate film

These photographs were all taken with perhaps my all-time favourite Polaroid film: Polaroid 100 Chocolate. When you peel the negative away from the print from the back instead of the font, it leaves part of the mask behind, hence the mottled grey and purple frames on these photos. (This technique works best with 100 Chocolate film, though it can also be used on Polaroid 669 film with nice results.)

I now just have one pack of this film left in the fridge… but will I ever be able to break into my last ever pack… we'll see!

Other type of pack film

Emulsion life prints

One of the things that I love about Polaroid photography is all the amazing things you can do with a Polaroid print after you have taken it. This technique only works with Polaroid 669 colour film. Basically you just put the print in a tray of water heated to around 70 degrees. After a few minutes the emulsion layer will lift of the print base and float in the in the water. You can then slide a piece of paper under the emulsion, lift the paper out of the water, and the emulsion layer will stick to the piece of paper.

Below you can see the original print on Polaroid 669 film, and the resulting emulsion lift print on Fabriano Artistico Traditional White Hot Pressed paper. The choice of paper is important as the texture of the paper will show through the emulsion layer.